The Afterlife of the Crack Era

The crack cocaine epidemic that swept through the United States in the 1980s and 1990s left behind more than headlines and statistics; it reshaped urban landscapes, legal systems, and generational pathways in ways that continue to define our work as planners, lawyers, educators, and community advocates. The crack era created what scholars of carceral geography call a “spatial fix for crisis,” where political and economic instability was managed through surveillance, policing, and incarceration rather than investment, healing, and care. The neighborhoods that absorbed these shocks were already vulnerable places long marked by redlining, disinvestment, and racial segregation, and the compounded effect was a deep social fracture that persists into 2025.

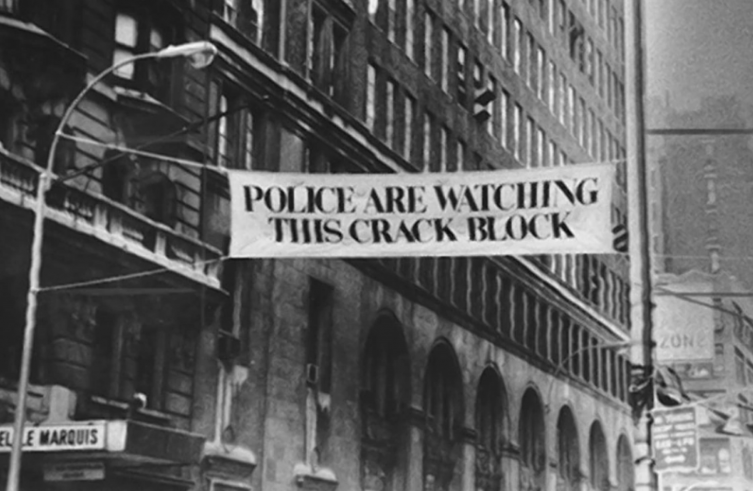

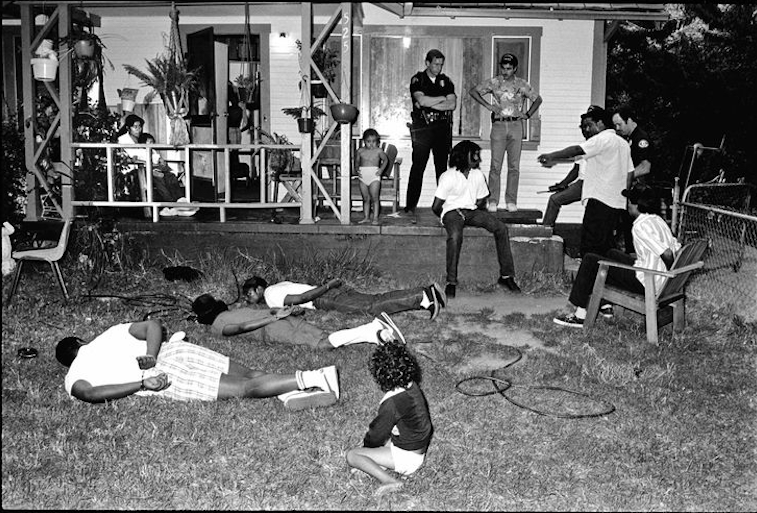

When crack markets emerged, violence escalated not only because of the drug trade itself but because of the militarized response to it. Law enforcement agencies flooded cities with weapons and tactics once reserved for war. Firearms became a feature of daily life in many neighborhoods, reshaping both interpersonal and institutional relationships to safety. The “war on drugs” blurred the line between security and punishment, making the presence of police feel less like protection and more like occupation. This spatial and psychological pattern continues to reverberate in how communities experience urban renewal, zoning, and development today.

The policies that accompanied the crack era mandatory minimums, “three strikes” laws, and the 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, turned poverty and addiction into criminal categories. These laws extracted people from their neighborhoods at mass scale, removing the very fabric of community life: parents, mentors, workers, teachers, and caretakers. What was described as crime control was, in effect, the reorganization of racial capitalism through the carceral state. Incarceration became both a spatial and social condition shaping who could live where, who could own property, and who could belong.

Families fractured under the weight of incarceration and addiction. The children of those decades grew up navigating grief, stigma, and economic displacement, often without the adults who once stabilized their homes. Teachers, social workers, and health professionals became first responders to trauma that was never acknowledged as public policy harm. In classrooms and courtrooms, the children of the crack era encountered systems unprepared to see them as survivors. Many of those children are now middle-aged, still working to rebuild trust, raise their own families, and reclaim dignity within institutions that once wrote them off.

For planners and policy professionals, the built environment tells this story in brick, concrete, and zoning code. Vacant lots where homes once stood. Schools closed for “underperformance.” Corridors that shifted from thriving main streets to overpoliced zones. Public housing demolished under the banner of revitalization. These transformations reveal what abolitionist planners describe as “the reproduction of disposable people” through land use and regulation. Planning became, at times, a quiet partner in disappearance erasing the physical and cultural memory of the communities that bore the brunt of the crack era.

Yet within this landscape of harm, there has also been an ongoing current of resistance and care. The same communities that were criminalized have continued to build models of healing violence interruption programs, restorative justice circles, reentry networks, mutual aid collectives, and faith-based healing ministries. These efforts represent what planning scholars call reparative praxis: the combination of radical honesty, acknowledgment, and collective action that transforms institutional complicity into shared responsibility. They remind us that recovery from state violence is not a technical challenge but a spiritual and relational one.

To confront the afterlife of the crack epidemic, our professions must take up the work of repair not as metaphor but as method. This means addressing the material conditions that persist: criminal records that still block employment and housing, neighborhoods excluded from investment, schools unprepared to support intergenerational trauma. It means creating pathways for those most affected to lead the design of recovery, from zoning reforms to mental health services. It means expanding how we define “public safety” to include freedom from displacement, access to care, and the restoration of community governance.

As educators and lawyers, this requires teaching the crack era not only as a historical episode but as a living structure of racialized planning and policy. As planners, it asks us to map the long arc of disinvestment alongside the carceral geographies that emerged from it. As students and organizers, it challenges us to see our research and advocacy as forms of remembrance and repair.

In planning scholarship, the call to “imagine otherwise” has become an invitation to disrupt the white spatial imaginary that normalizes Black dispossession. Similarly, Indigenous planning frameworks urge us to locate healing in land, kinship, and sovereignty, not in bureaucratic approval processes. The lessons of the crack era point us toward the same horizon: community-led restoration rooted in dignity and self-determination.

Repair begins when we restore relationships between neighbors, across generations, and within the institutions that failed them. Healing follows when we design systems that honor grief, rebuild trust, and reimagine belonging. These are not symbolic gestures. They are the substance of a kind of planning practice—one that sees the city not as a container for capital, but as a site for reckoning, remembering, repair and renewal.